You Claim Ocean Vuong, but Not His Past

I adore Ocean Vuong, as do many Vietnamese. We claim him because he carries a last name we can pronounce—one that Americans cannot. But our pride has a limit, one that renders his past invisible.

Ocean Vuong’s recent interview with the New York Times journalist, David Marchese, is among the most poignant podcasts I have ever listened to—and for Marchese, “one of the most emotionally intense interviews” he has ever undertaken.

In the prelude that leads up to the interview, David Marchese describes Vuong’s journey as “a classic American success story,” one that entails the remarkable rise of a Vietnamese refugee arriving in Hartford, working low-paying jobs, and enduring the cultural and personal alienation before becoming “one of the country’s [America] most esteemed poets.”

Ocean Vuong is a recognized and celebrated name among the young cosmopolitan population in America and Vietnam alike. In America, Ocean Vuong is the symbol of progressive politics and the cultural shift to include the historically marginalized people (i.e., queer and immigrant identity). Vuong’s books have been the flashpoint of many heated cultural debates, mostly about the appropriateness of his work for young people.

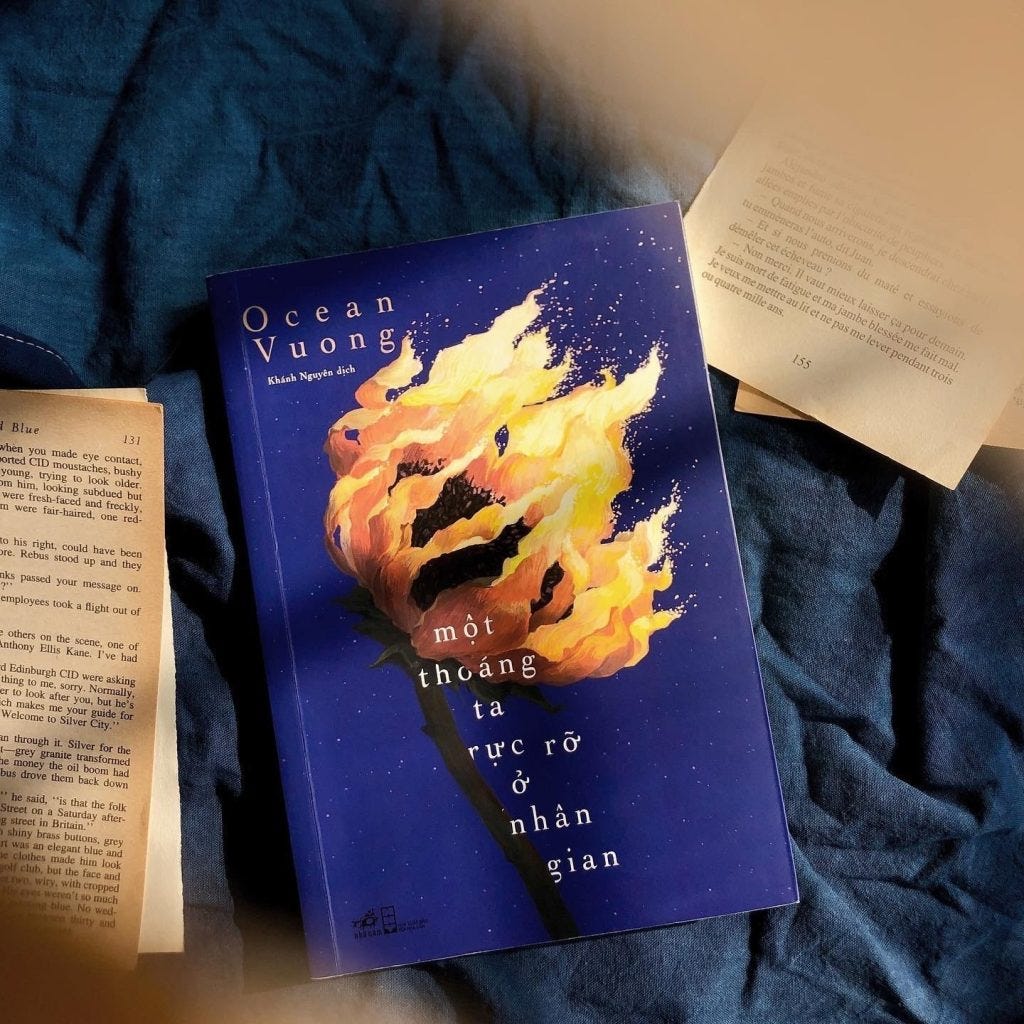

In Vietnam, Ocean Vuong is a source of pride and, at times, aesthetics. His debut novel, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, after being translated into Vietnamese, his mother tongue, rapidly became an emblem of progressive youth. It was the book that everyone was seen flaunting, posting about on social media, and talking about (but not always discussing). And how can they not: it’s a gorgeous book. For Vietnamese (myself included), the book allows them to be entertained with frequent pulses of familiarity—a Vietnamese idiom, the voiceless maternal care, and more—something that they don’t often find in a foreign-language novel. Moreover, Vuong’s language and subject matter boldly introduced Vietnamese audiences to a raw, unapologetic, and ardent exploration of queerness and intimacy.

It’s a beautiful book, and the Vietnamese audience rightfully embraces it.

Yet, in the Vietnamese discourse surrounding Ocean Vuong, crowded by the myriad of accolades Vuong has been awarded in his career, by the peculiar name he bears (Ocean), and by Andrew Garfield’s professed desire to marry the author, one salient detail has been overlooked: his refugitive past. More specifically, the utterly grim circumstance Vuong family faced—the persecution of his biracial mother in post-1975 southern Vietnam—that forced them to the brink, leaving them no choice but to flee the country.

I write this in the wake of an excessive rise in nationalism in Vietnam as the country commemorates 50 years since national reunification. The national pride has grown so monstrously, it becomes grotesque and vilifies all those who do not share the modern Vietnamese state’s memory and past. Technically, that includes the story of Ocean Vuong.

But you must imagine—and I truly hope that you can—what an excruciating decision that must have been, for a mother, to bring her two-year-old son, all she had, to seek refuge in a faraway place where she, an illiterate who does not speak the language of the land, knew that life would be beyond grueling. America is the promised land for many. But would she have made that onerous journey had she not been harassed by the police for nothing but her existence, the ineluctable nature that her skin was of mixed colors and the blood that ran in her veins was, by the Vietnamese standard, tainted.

“I think writing helped me understand that although you can technically be a victim—you can be a victim of war; you can be a victim of domestic violence, child abuse—but whether you live in victimhood_ or not is up to you. We can’t change what happens to us; (but) we can change how we live in order to have a successful life.”

— Ocean Vuong, in an Amanpour and Company interview

I doubt that Ocean Vuong’s mother was the only one who suffered that fate. But this exact story, one shared by many, has been muffled by modern-day Vietnamese.

There was a generation that left Vietnam not merely for the betterment of their own future, but because it was their only choice—not all, but for many of them, that was the case. They were then criticized by those who stayed, many of whom never mustered up sufficient sympathy to even try to empathize with the other group. Decades later, their offspring, including Vuong, crafted artistic legacies deeply informed by those painful departures. Yet now, as Vietnamese society selectively embraces these authors—Ocean Vuong is “safe” due to his aesthetic distance from explicit communist critique; Nguyen Thanh Viet is similarly “safe” because of his liberal, softly peripheral communist ideology, a black sheep of the Californian Vietnamese community—the broader historical context is often quietly erased, sanitized, or conveniently forgotten.

Ocean Vuong, a practicing Zen Buddhist, has never criticized communism (at least not that I am aware of), which makes him, in the eyes of modern Vietnamese, a good Vietnamese American.

But can we—myself included, a communist Vietnamese—blame him, really, if he had?

I fast-forwarded through Thuỳ Minh’s interview of Ocean Vuong on VietCetera’s flagship podcast, Have A Sip. (I should say: I have never really liked Thuỳ Minh. There is, at times, a lot of times, a degree of ingenuity and insensitivity that is so permeated in the way Thuỳ Minh presents herself that I find as a slight…ick).

Toward the end of the interview, when Vuong mentioned his request for Nhã Nam, the publisher of the Vietnamese translated edition of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, to record the audiobook version in a Southern accent, Thuỳ Minh gave Vuong the look. She then asked, with the look still: “What’s wrong with my accent?”

To respond, Vuong explained the class and power structure in language: how the book is “a miền Nam book” and there is a “power” in the Northern accent that manifests itself differently in the Southern accent.

Ocean Vuong probably understands, more than most people, the power—or inpower—of his identity, language, and voice. And so, he guards his language with his newfound power, as “America’s most esteemed poet,” with the clarity of someone who rises from nothing.

To recognize and appreciate Ocean Vuong, to treasure his works, requires more than just social media posts. It demands the humility to trace back his scars, the empathy to reckon with the choices that shaped his family’s exile, and the honesty to name what forced them out.

Like reading his works, we should open ourselves to discomfort.

Cathy Park Hong’s essay Minor Feelings has some great thoughts on how (many) readers have failed to take seriously both Voung’s queerness and his class experiences in favor of “multicultural” (read capitalist) reading

Ocean is incredibly moving. All of his works need you to engage with such openess and reflection. It's beyond being deep or just wanting to look like you read widely. He really challenges me to sit with it.